![]()

Here we see my host and friend, Justo Jacanamijoy, sharing talk and chicha with Fidel, his brother-in-law.

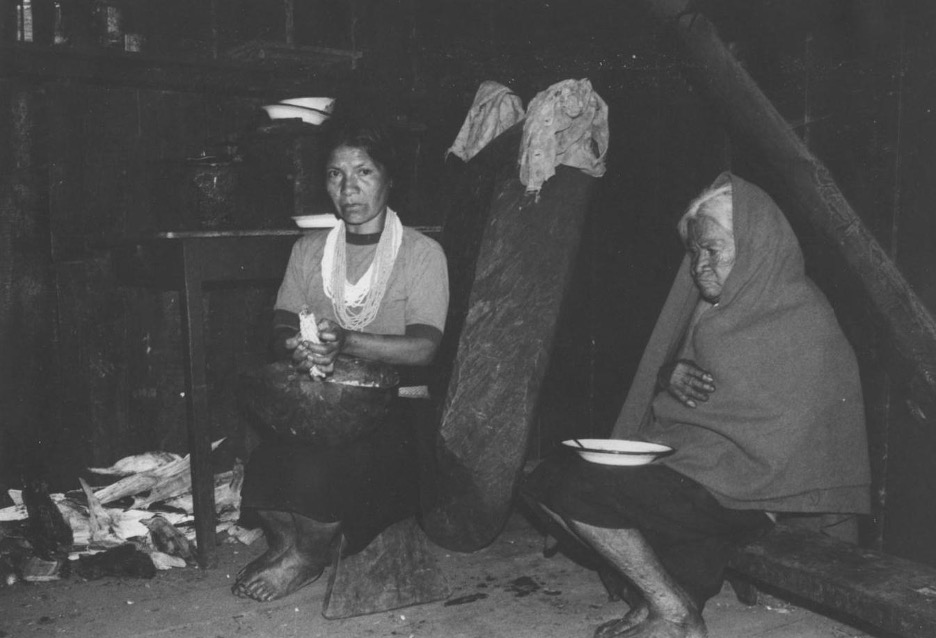

And here is a photo I took of María Juajibioy and her mother doña Concepción, by the tulpa, the cooking fire.

![]()

During the course of more than a quarter-century involvement with the two

indigenous communities of the Sibundoy Valley, the Kamënstá (also known as

the Kamsá) and the Inga (also known as the Ingano), I have sought to document

and decipher the rich fabric of verbal expressive forms as they implicate the

spiritual life and cosmology of these peoples, and inform their everyday

lives as well as their carnival celebrations. I have had the rare privilege

to document a living mythic narrative tradition, to chart the contours of a

ceremonial speech genre, and to explore the deeper meanings of proverb-like

"sayings of the ancestors." This work of cultural recuperation continued

for many years in Bloomington with my compadre, Francisco Tandioy; together

with Juan Eduardo Wolf (and with contributions from many Inga students at IU),

we created a language-learning text, in both English and Spanish versions.

Inga Rimangapa Samuichi: Vengan a hablar la lengua inga. Center for Latin

American and Caribbean Studies, Indiana University, 2012. (With Francisco

Tandioy Jansasoy and Juan Eduardo Wolf).

Inga Rimangapa Samuichi: Speaking

the Quechua of Colombia. Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies,

Indiana University, 2011. (With Francisco Tandioy Jansasoy and Juan Eduardo Wolf).

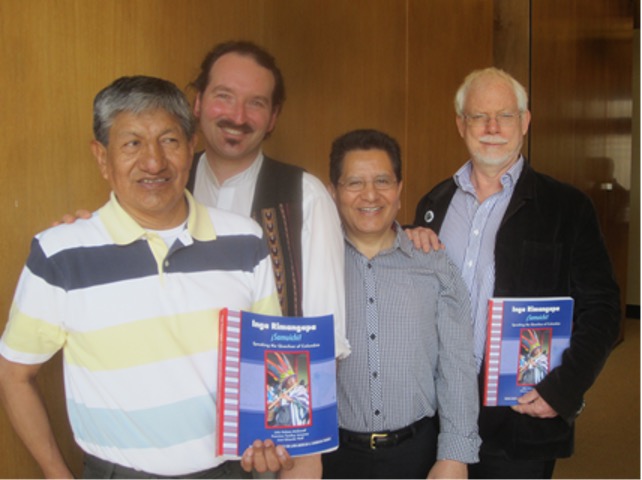

Francisco Tandioy, Juan Eduardo Wolf, Serafín Coronel-Molina, and John McDowell,

at a celebration of the Inga text — friend Serafín delivered a wonderful appreciation of the book.

So Wise Were Our Elders

Taita

Bautista Juajibioy Chindoy, six times gobernador of the Kamsá

indigenous community, was one of several elders who contributed their time

and knowledge to helping me understand the birth of civilization in the

Sibundoy Valley. A wise and generous man, he would be out in the

afternoons laughing at the beauty of the flowers surrounding his house. I

enjoyed the many hours I spent in his company, and in the company of his

wife, Concepción, and their many children and grandchildren. It was Taita

Bautista who explained to me about yebets tempo, the time of

darkness, which came to an end with the first rising of the sun. He took

delight in talking about kaka tempo, the raw time, when people had

no fire and ate everything uncooked. He concluded his sketch with the

arrival of the missionaries, initiating the modern age in Sibundoy

history. Taita Bautista was a devout Catholic, and towards the end of his

life he refused to tell me stories about the ancestors, calling such

stories, in Spanish, pura paja, that is to say, nothing but trash.

Taita

Bautista Juajibioy Chindoy, six times gobernador of the Kamsá

indigenous community, was one of several elders who contributed their time

and knowledge to helping me understand the birth of civilization in the

Sibundoy Valley. A wise and generous man, he would be out in the

afternoons laughing at the beauty of the flowers surrounding his house. I

enjoyed the many hours I spent in his company, and in the company of his

wife, Concepción, and their many children and grandchildren. It was Taita

Bautista who explained to me about yebets tempo, the time of

darkness, which came to an end with the first rising of the sun. He took

delight in talking about kaka tempo, the raw time, when people had

no fire and ate everything uncooked. He concluded his sketch with the

arrival of the missionaries, initiating the modern age in Sibundoy

history. Taita Bautista was a devout Catholic, and towards the end of his

life he refused to tell me stories about the ancestors, calling such

stories, in Spanish, pura paja, that is to say, nothing but trash.

Francisco Tandioy Jansasoy is my compadre and longtime friend and partner in the

quest to explore and recuperate the culture of his community, the

Santiagueño Inganos, speakers of the northernmost representative of the

Quichua language family. A native of the vereda of Vichoy, Francisco was raised in the Sibundoy Valley, but

went off to high school in the nearby city of Ipiales. He eventually

became a professor of languages at the Universidad de Nariño, teaching

both English, learned while doing the MA in Linguistics at IU, and Inga,

his native tongue.

Francisco Tandioy Jansasoy is my compadre and longtime friend and partner in the

quest to explore and recuperate the culture of his community, the

Santiagueño Inganos, speakers of the northernmost representative of the

Quichua language family. A native of the vereda of Vichoy, Francisco was raised in the Sibundoy Valley, but

went off to high school in the nearby city of Ipiales. He eventually

became a professor of languages at the Universidad de Nariño, teaching

both English, learned while doing the MA in Linguistics at IU, and Inga,

his native tongue.

My compadre returned to Bloomington in January of 2003 to

teach Quichua and to collaborate with me as a Fellow of the IU Institute

for Advanced Study. We call our project Atunkunapa

Iuiai Iachachiska, roughly "Wisdom of the Inganos." The plan is to

develop a set of resources for scholarly investigation as well as

dissemination to the community. We are working on a wide variety of texts

including mythic narrative, oral history, ceremonial speeches, customs,

advice and counsel, the Ingano carnival, and the knowledge of the Sibundoy

native doctors.

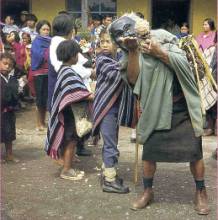

Return of the First People

Carnival in the Sibundoy Valley of Colombia

is a special event that enables people to experience and affirm their membership

in the indigenous communities. The Sibundoy Valley is home to two indigenous

communities, the Kamsá and Ingano, as well as a sizable population of

non-Indian Colombians. This part of our exhibit tells of carnival among the Kamsá.

Carnival in the Sibundoy Valley of Colombia

is a special event that enables people to experience and affirm their membership

in the indigenous communities. The Sibundoy Valley is home to two indigenous

communities, the Kamsá and Ingano, as well as a sizable population of

non-Indian Colombians. This part of our exhibit tells of carnival among the Kamsá.

--Klistrinyi! Klistrinyi! Celebrate the Carnival!--

The Kamsá carnival extends over several days, with Tuesday as the day of

public display, when the Indians gather and parade from the countryside to

the center of Sibundoy town. They make a complete turn around the plaza,

enter the church, dance in the cabildo (the tribal council office),

and eventually drift back to the indigenous settlements. For several days

thereafter small carnival troops travel from house to house, receiving

food and drink from the hosts, making music and dancing. As carnival comes

to a close, people take leave of one another saying, "Wataskama," a

prayerful wish to live another year so that they might enjoy carnival one

more time.

The Kamsá carnival extends over several days, with Tuesday as the day of

public display, when the Indians gather and parade from the countryside to

the center of Sibundoy town. They make a complete turn around the plaza,

enter the church, dance in the cabildo (the tribal council office),

and eventually drift back to the indigenous settlements. For several days

thereafter small carnival troops travel from house to house, receiving

food and drink from the hosts, making music and dancing. As carnival comes

to a close, people take leave of one another saying, "Wataskama," a

prayerful wish to live another year so that they might enjoy carnival one

more time.

Three Carnival Texts

Three traditional forms of verbal art -- singing, storytelling, and chanting -- are used to bring about carnival among the Kamsá. In traditional verbal forms like these, people often reveal concerns, attitudes and perceptions that underlie their actions. Let's see what we can learn about Kamsá carnival from these forms.

The Carnival Song

"Klistrinyi" is known to every man, woman and child in the Kamsá settlements. Like other carnival songs, it is only sung between All Saints' Day in Novermber and carnival in February. The tune is anchored in a steady pulse of strong, evenly-spaced downbeats. Its melody features several phrases working their way from higher to lower pitches. The carnival song pours out in a haphazard fashion, as individual singer-performers are inspired to burst into song. The carnival-goers can be better described as musician-dancers, for each of them makes his or her own contribution to the enveloping wall of sound even as they move about keeping step with the pulse of the music.

Mythic Narratives

The Kamsá people have produced a mythology of great beauty and fascination, telling of the days of the ancestors and how civilization was established in the Sibundoy Valley. Many mythic tales are told: of Wangetsuma, who brought so much knowledge; of the First People, who showed everyone how to live; of animal suitors and tricksters, who tried to enter the human family but were rejected; of the spirit realm, reached through dreams and visions. Carnival dress, such as the feathered crowns, often alludes to these myths. It becomes clear that carnival is not only about having a good time, but also about exploring and renewing the sources of community.

The Carnival Blessing

These chants are performed as persons of lower social class ask for a blessing from their superiors. Formal speeches are improvised using a distinctive way of speaking known as the ritual language, which creates a prayer-like effect. Ritual language speeches make frequent reference to God, the Virgin Mary, and the ancestors, asking them to insure health and prosperity for one and all. By means of these chants, the community is presented as one big family, and all relationships between individuals are recast as idealized forms of kinship.

Experiencing Kamsá Carnival

The carnival experience is a powerful one, loaded with sensory stimulation and leading towards strong emotional involvement. The musician-dancers imbibe large quantities of chicha, the corn beer that is brewed by the women to fuel the carnival. On all sides are companions decked out in the colorful feathers, beads, and sashes of carnival. The loud vibrations of the larger drums engrave an echo of this insistent pulse that reverberates in people's heads days after carnival is over. These visual, auditory, and liquid stimulants converge to transport carnival participants to a special realm of reality, one that lies beyond the boundaries of normal experience. And what is it that people envision under the influence of carnival? It would appear to be nothing less than the very founding of their civilization. Kamsá cosmology tells of an ancestral period when the first humans interacted with celestial deities such as the sun, moon, and thunder at the very dawn of time. These First People conquered a wild spiritual universe and then established the norms of proper society. They taught early ancestors what foods they should eat and how they should reproduce, and they established forever the boundary between animals and humans. It is this long-ago turning point in cosmic time that is celebrated during Kamsá carnival, this moment when civil society emerged out of a primordial chaos.

![]()

Carnival

is best appreciated when experienced in all its intensity. The

true carnival spirit demands participation, not mere

observation. In an effort to convey something of the thrill of

the carnival experience, I have included an excerpt from my field

journal.

Carnival

is best appreciated when experienced in all its intensity. The

true carnival spirit demands participation, not mere

observation. In an effort to convey something of the thrill of

the carnival experience, I have included an excerpt from my field

journal.

![]()

" We have entered the house of the aquacil mayor, one of the chief officers of the cabildo, the community organ of self-government. We are a singing, dancing horde, maybe one hundred of us, musician-dancers arrayed in feathered crowns and traditional ponchos. At every step we are presented gourd cups of chicha (maize beer) by fellow musician-dancers porting larger aluminum containers of the refreshing and intoxicating beverage."

"On all sides circulate flutists, sporting flutes ranging from barely a foot long to a yard or more, each intoning (but not in unison) the carnival melody. Other dancers beat the steady carnival rhythm on drums or keep the same beat with seed rattles or jars filled with stones. From time to time one captures the sweet tones of a harmonica floating nearby, and blasts from the hollowed sugar-cane stalks and horn trumpets assault the ears from all directions. Here and there someone sings a verse from the carnival song, and the web of sound is punctuated with the cry: "Klistrinyi, klistrinyi!" ("celebrate the carnival!")

"Our motley carnival orchestra has no need of conductor, score or audience; it is held together by the isochronic rhythm and the plaintive strains of the carnival melody. In the midst of all this fanfare a remarkable transformation occurs: the ecstatic dancers take on an altered identity as ancestral spirit beings, and we are transported to the cosmic juncture when the first human beings wrested spiritual dominion away from the aucas, the heathen savages of the region. It is carnival time in the Sibundoy Valley and the ancestral spirits once again wander the earth." -- John McDowell

![]()

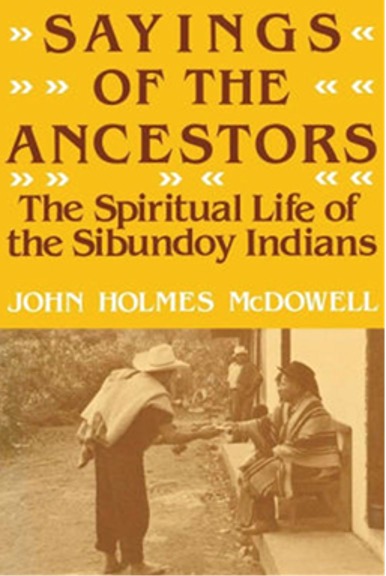

Sayings of the Ancestors

Publisher's blurb:

Publisher's blurb:

The Sibundoy valley of southwestern Colombia is the home of a unique Indian

culture—one that blends Incan elements with those of the aboriginal natives.

Moreover, Sibundoy bridges two domains, the Andean highlands and the Amazonian

basin, and inter-mixed with all of these elements are European influences,

particularly folk and orthodox Catholicism. From this cultural enclave,

John McDowell presents here a body of oral material collected from the Santiago

Ingano community.

This corpus of material is made up of some 200 "sayings of the ancestors,"

proverb-like statements, many concerned with dreams and the forecasting of

future events. From an analysis of these sayings emerges a cosmological

view of the Sibundoy Indians, a glimpse of their spiritual world. It is a

world where spirits constantly impinge on the activities of everyday life.

It is a world where the sayings can both warn of spiritual sickness and offer

the way to spiritual health. For the Sibundoy the sayings go back to the

first people, the "ancestors," who established for all time the models for

a proper life. The study of the sayings is rounded out with references to

the parallel fields of mythology and folk medicine as these contribute to

a clearer understanding of their roles and functions in Sibundoy life.

Sayings of the Ancestors provides a fascinating body of original folkloric

and ethnographic material from a unique cultural locus. It is also an

engrossing demonstration that what seems a miscellaneous group of small

beliefs can be seen as the components of a larger world-order. The book

and its interpretive findings will be a valuable resource for folklorists,

anthropologists, and many Latin Americanists.

Last Modified Jan 18, 2022